Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (August 28, 1749 – March 22, 1832) was a German writer, scientist, theatre director, critic, a master of poetry, drama, and the novel.

His works include plays, poetry, literature, and aesthetic criticism, as well as treatises on botany, anatomy, and colour. He is widely regarded as the greatest and most influential writer in the German language, his work having a profound and wide-ranging influence on Western literary, political, and philosophical thought from the late 18th century to the present day.

Early Life and Education (1749–1771)

Goethe was born into a wealthy bourgeois family in Frankfurt, Germany. His father, Johann Kaspar Goethe, was a man of leisure who had inherited money from his own father, and his mother, Katharina Elisabeth, was the daughter of the most senior official in Frankfurt. The couple had seven children, although only Goethe and his sister Cornelia lived to adulthood.

His father and private tutors gave the young Goethe lessons in common subjects of their time, especially languages (Latin, Greek, Biblical Hebrew, French, Italian, and English. Goethe also received lessons in dancing, riding, and fencing. Johann Caspar, feeling frustrated in his own ambitions, was determined that his children should have all those advantages that he had not.

Although Goethe’s great passion was drawing, he quickly became interested in literature; Friedrich Gottlieb Klopstock (1724–1803) and Homer were among his early favorites. He had a devotion to theater as well, and was greatly fascinated by puppet shows that were annually arrangedin his home; this became a recurrent theme in his literary work Wilhelm Meister’s Apprenticeship.

He also took great pleasure in reading works on history and religion. He writes about this period:

“I had from childhood the singular habit of always learning by heart the beginnings of books, and the divisions of a work, first of the five books of Moses, and then of the Aeneid and Ovid’s Metamorphoses. … If an ever busy imagination, of which that tale may bear witness, led me hither and thither, if the medley of fable and history, mythology and religion, threatened to bewilder me, I readily fled to those oriental regions, plunged into the first books of Moses, and there, amid the scattered shepherd tribes, found myself at once in the greatest solitude and the greatest society.”

Accordingly, Goethe started at university in Leipzig in 1765 to study law. There he fell in love with Anne Katharine Schönkopf, the daughter of an innkeeper, and dedicated a volume of joyful poems to her called Annette. Ultimately, however, she married another man. Goethe’s first mature play, The Partners in Crime (Die Mitschuldigen, 1787), is a comedy depicting a woman’s regrets after she married the wrong man. Upset by her refusal of him and having fallen ill with tuberculosis, Goethe returned home to convalesce.

In 1770 he moved to Strasbourg to finish his law degree. It was there that he met philosopher Johann Gottfried Herder, the leader of the Sturm und Drang (“Storm and Stress”) intellectual movement. The two became close friends. Herder permanently impacted Goethe’s literary development, kindling an interest in Shakespeare and introducing him to a developing philosophy that language and literature are in fact expressions of a highly specific national culture. Herder’s philosophy stood in contrast to Hume’s assertion “that mankind are so much the same in all times and places that history informs us of nothing new or strange.” This idea inspired Goethe to travel the Rhine Valley collecting folk songs from local women in an effort to more fully grasp German culture in its “purest” form. In the small village of Sessenheim, he met and fell deeply in love with Friederike Brion, whom he would leave just ten months later, fearful of the commitment of marriage. The theme of the woman abandoned appears often in Goethe’s literary works, most notably in the end of Faust I, leading scholars to believe that this choice weighed heavily on him.

Sturm und Drang (1771–1776)

These were some of Goethe’s most productive years, seeing a high production of poetry as well as several play fragments. However, Goethe began this period intent on law: he was promoted to Licentitatus Juris and set up a small law practice in Frankfurt. His career as a lawyer was notably less successful than his other ventures, and in 1772, Goethe traveled to Darmstadt to join the supreme court of the Holy Roman Empire to gain more legal experience. On the way he heard a story about a famous 16th century dashing highwayman-baron who achieved fame during the German Peasants’ War, and within weeks Goethe had written the play Götz von Berlichingen. The play ultimately sets the foundations for the archetype of the Romantic hero.

In Darmstadt he fell in love with the already-engaged Charlotte Buff, called Lotte. After spending a tortured summer with her and her fiancé, Goethe heard about a young lawyer who shot himself, for reasons rumored to be love of a married woman. These two events probably inspired Goethe to write The Sorrows of Young Werther (Die Leiden des jungen Werthers, 1774), a novel whose release almost immediately catapulted Goethe into literary stardom. Told in the form of letters written by Werther, the intimate depiction of the main character’s mental collapse, told in the first person, captured imaginations across Europe. The novel is a hallmark of the Sturm und Drang era, which honored emotion above reason and societal mores. Although Goethe was somewhat dismissive of the Romantic generation that came directly after him, and the Romantics were themselves often critical of Goethe, Werther caught their attention and is thought to be the spark that ignited the passion for Romanticism, which swept across Europe at the turn of the century. Indeed, Werther was so inspiring that it sadly remains notorious for having set off a wave of suicides across Germany.

De to his reputation, in 1774 when he was 26, Goethe was invited to the court of the 18-year-old duke of Weimar, Karl August. Goethe impressed the young duke and Karl August invited him to join the court. Although he was engaged to be married to a young woman in Frankfurt, Goethe, probably feeling characteristically stifled, left his hometown and moved to Weimar, where he would remain for the rest of his life.

Weimar (1775–1788)

Karl August supplied Goethe with a cottage just outside of the city gates, and not long thereafter made Goethe one of his three counselors, a position that kept Goethe busy. He applied himself with limitless energy and curiosity to court life, quickly rising the ranks. In 1776, he met Charlotte von Stein, an older woman already married; even still, they formed a deeply intimate bond, though never a physical one, that lasted for 10 years. During his time in the court of Weimar, Goethe put his political opinions to the test. He was responsible for the War Commission of Saxe-Weimar, the Mines and Highways commissions, dabbled in the local theatre, and, for a few years, became the chancellor of the duchy’s Exchequer, which made him briefly more or less prime minister of the duchy. Due to this amount of responsibility, it soon became necessary to ennoble Goethe, undertaken by Emperor Joseph II and indicated by the “von” added to his name.

In 1786-1788, Goethe was given permission by Karl August to travel to Italy, a trip that would prove to have lasting influence on his aesthetic development. Goethe undertook the trip due to his renewed interest in classical Greek and Roman art prompted by the work of Johann Joachim Winckelmann. Despite his anticipation for the grandeur of Rome, Goethe was severely disappointed by the state of its relative dilapidation, and left not long thereafter. Instead, it was in Sicily that Goethe found the spirit he was searching for; his imagination was captured by the island’s Greek atmosphere and he even fancied that Homer could have come from there. During the trip he met artists Angelica Kauffman and Johann Heinrich Wilhelm Tischbein, as well as Christiane Vulpius, who would soon become his mistress. Although the journey was not extremely productive literarily for Goethe, the first year of this two-year journey he chronicled in his journal and later revised as an apology against Romanticism, published as the popular Italian Journey (1830). The second year, spent mostly in Venice, remains a mystery to historians; what is clear, however, is how this trip inspired a deep love of Ancient Greece and Rome that was to have a lasting influence on Goethe, especially in his founding of the genre Weimar Classicism.

French Revolution

Upon Goethe’s return from Italy, Karl August allowed him to be relieved of all administrative duties and instead focus solely on his poetry. The first two years of this period saw Goethe close to finishing a complete collection of his works, including a revision of Werther, 16 plays (including a fragment of Faust), and a volume of poetry. He also produced a short collection of poetry called Venetian Epigrams, containing some poems about his lover, Christiane. The pair had a son and lived together as a family, but were unmarried, a move that was frowned upon by Weimar society at large. The couple was unable to have more than one child survive to adulthood.

The French Revolution was a divisive occasion within the German intellectual sphere. Goethe’s friend Herder, for example, was heartily in support, but Goethe himself was more ambivalent. He remained true to the interests of his noble patrons and friends while still believing in reform. Goethe accompanied Karl August multiple times on campaigns against France, and was shocked by the horrors of war.

Despite his newfound freedom and time, Goethe found himself creatively frustrated and produced several plays that did not succeed on the stage. Instead he turned to science: he produced a theory about the structure of plants and of optics as an alternative to Newton’s, which he published as Optical Essays and “Essay in the Elucidation of the Metamorphosis of Plants.” However, neither of Goethe’s theories is upheld by modern-day science.

Weimar Classicism and Schiller (1794–1804)

In 1794, Goethe became friends with Friedrich Schiller, one of the most productive literary partnerships in modern Western history. Though the two had met in 1779 when Schiller was a medical student in Karlsruhe, Goethe had remarked somewhat dismissively that he felt no kinship with the younger man, considering him talented but a bit of an upstart. Schiller reached out to Goethe suggesting that they start a journal together, which was to be called Die Horen (The Horae). The journal received mixed success and, three years in, ceased production.

The two, however, recognized the incredible harmony they found in each other and remained in creative partnership for ten years. With Schiller’s help, Goethe finished his very influential Bildungsroman (coming-of-age story), Wilhelm Meister’s Apprenticeship (Wilhelm Meisters Lehrjahre, 1796), as well as Hermann and Dorothea (Hermann und Dorothea, 1782-4), one of his most lucrative works, among other shorter masterpieces in verse. This period also saw him taking up work again on perhaps his greatest masterpiece, Faust, though he was not to finish it for several decades.

This period also saw the expression of Goethe’s love of classicism and his hope to bring the classical spirit to Weimar. In 1798, he started the journal Die Propyläen (“The Propylaea”), which was meant to give a place for the exploration of the ideals of the antique world. It lasted only two years; Goethe’s almost rigid interest in classicism at this time went against the Romantic revolutions being carried out across Europe, and Germany in particular, in art, literature, and philosophy. This also reflected Goethe’s belief that Romanticism was simply a beautiful distraction.

The next few years were difficult for Goethe. By 1803, Weimar’s flourishing period of high culture had passed. Herder died in 1803, and even worse, Schiller’s death in 1805 left Goethe deeply grieving, feeling he had lost half of himself.

Napoleon (1805–1816)

In 1805, Goethe sent his manuscript of color theory to his publisher, and the next year he sent the completed Faust I. However, war with Napoleon delayed its publication for two more years: in 1806, Napoleon routed the Prussian army at the Battle of Jena and took over Weimar. Soldiers even invaded Goethe’s house, with Christiane displaying great bravery organizing the defense of the house and even tussling with the soldiers herself; luckily they spared the author of Werther. Days later, the two finally made official their 18-year relationship in a marriage ceremony, which Goethe had resisted due to his atheism but now chose perhaps to ensure Christiane’s safety.

The period post-Schiller was distressing for Goethe, but also literarily productive. He started a sequel to Wilhelm Meister’s Apprenticeship, called Wilhelm Meister’s Journeyman Years (Wilhelm Meisters Wanderjahre, 1821), and finished the novel Elective Affinities (Die Wahlverwandtschaften, 1809). In 1808, he was made a Knight of the Legion of Honor by Napoleon, and began warming up to his regime. However, Christiane died in 1816, and only one son survived to adulthood of the many children she birthed.

Later Years and Death (1817–1832)

By this time Goethe was getting old, and turned to setting his affairs in order. Despite his age, he continued producing many works; if there is one thing to be said about this mysterious and inconsistent figure, it is that he was prolific. He finished his four-volume autobiography (Dichtung und Wahrheit, 1811-1830), and finished another collected works edition. In 1818, just before he turned 74, he met and fell in love with the 19-year-old Ulrike Levetzow; she and her family declined his marriage proposal, but the event prompted Goethe to compose more poetry. In 1829, Germany celebrated the 80th birthday of its most renowned literary figure.

In 1830, despite withstanding the news of the deaths of Frau von Stein and Karl August a few years prior, Goethe fell seriously ill upon hearing that his son had died. He recovered long enough to finish Faust in August 1831, which he had worked on throughout his life. A few months later, he died of a heart attack in his armchair. His last words, according to his doctor Carl Vogel [de], were, Mehr Licht! (More light!), but this is disputed as Vogel was not in the room at the moment Goethe died.

Influence and Legacy

Goethe had a great effect on the nineteenth century. In many respects, he was the originator of many ideas which later became widespread. He produced volumes of poetry, essays, criticism, a theory of colours and early work on evolution and linguistics. He was fascinated by mineralogy, and the mineral goethite (iron oxide) is named after him.

His non-fiction writings, most of which are philosophic and aphoristic in nature, spurred the development of many thinkers, including Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, Arthur Schopenhauer, Søren Kierkegaard, Friedrich Nietzsche, Ernst Cassirer, and Carl Jung.

George Eliot called him “Germany’s greatest man of letters… and the last true polymath to walk the earth.” Works span the fields of literature, theology, and humanism. People laud this magnum opus as one of the peaks of world literature. Other well-known literary works include his numerous poems, the Bildungsroman Wilhelm Meister’s Apprenticeship and the epistolary novel The Sorrows of Young Werther.

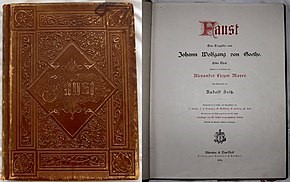

The Faust tragedy/drama, often called Das Drama der Deutschen (the drama of the Germans), written in two parts published decades apart, would stand as his most characteristic and famous artistic creation. Followers of the twentieth-century esotericist Rudolf Steiner built a theatre named the Goetheanum after him—where festival performances of Faust are still performed.