Throughout ancient times, wars have been an enduring facet of human history, with only a few intervals free from conflict. Once again, we find ourselves in a state of war, disconnected from God, ourselves, our roots, and ancestors, forgetting our primary responsibility of maintaining peace. Despite the universal yearning for peace, it remains elusive! Looking back at Vinča culture, and further exploring this not-so-accidentally found, culturally rich layer of Vinča, situated approximately 10.5 meters high, just 11 km from Belgrade – a most intriguing living tableau found in today’s Serbia, with its vertical reddish, yellow, dark, brown, and black hues of tools, dishes, jewelry, figurines, and other undisclosed secrets – it captivates our attention with its ‘large eyes’, and perhaps compels us to delve deeper and gain a more profound understanding of ourselves.

What is Vinča culture, and where and when did it originate?

Vinča culture signifies the Late Neolithic and Early Eneolithic era in Europe, spanning from 5300 to 4300 BC. It stands as the continent’s first civilization, extending over a territory larger than any other Neolithic culture in Europe. Technologically the most advanced prehistoric culture in the world, it witnessed the first industrial revolution, marking the dawn of the first modern era in human history.

How was Vinča culture discovered, a subject still relatively unknown globally?

Legend has it that an elderly man, named Pero, while traversing his land after a heavy rain in 1907, stumbled upon a beautiful figurine. Subsequently, he brought the figurine to the National Museum in Belgrade, leading archaeologists to uncover traces of a new culture later named Vinča.

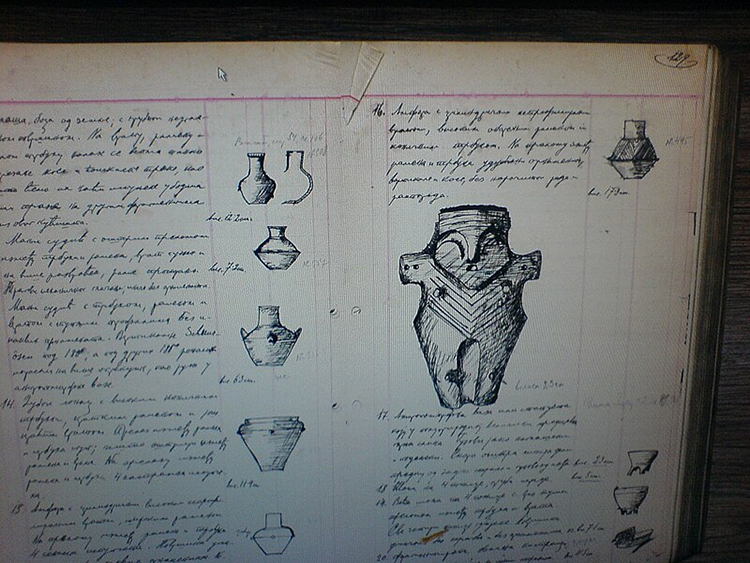

Named after the site of Vinča – Belo Brdo (t/n: White Hill), situated 11 km downstream from Belgrade on the Danube’s right bank, excavations began in 1908 under the guidance of Dr. Miloje Vasić, a professor at Belgrade University. Despite the economic challenges of the Kingdom of Serbia in 1908, Professor Vasić secured funds, commencing excavations on a 400 m² area.

With brief interruptions, the work continued until the outbreak of World War I, resuming in 1924 briefly, and finally halting due to a lack of funds. The excavations revealed eight Neolithic settlements, the oldest belonging to the Middle Neolithic period and the Starčevo culture.

In the 1930s, Vinca gained worldwide renown, with Miloje Vasić publishing the four-volume monograph Prehistoric Vinča in 1932 and 1936, concluding the second phase of research on this site.

Over the subsequent century, research confirmed the presence of Vinča culture’s common characteristics in several Eastern European countries: Bulgaria, Romania up to the Carpathians, Hungary, Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Macedonia, Montenegro and Greece, spread over the area of central Balkans, solidifying its status as the first and most comprehensively explored settlement in Europe.

What preceded its creation?

The Stone Age, a vast period lasting approximately 3.4 million years, concluded between 8700 and 2000 BC with the advent of metal processing. Divided into the Paleolithic, Mesolithic, Neolithic, and Eneolithic (Copper Age). The Paleolithic spanned from three million years BC to 10,000 BC, while the Mesolithic extended from the end of the Ice Age to the emergence of agriculture in the Neolithic.

According to most experts, a significant catastrophe occurred around 10,000 BC, marked by the melting of ice in central Europe, northern Asia, and the northern part of North America, resulting in rising sea levels.The water levels of Pacific rose by about 80 meters, and of the Atlantic by about 120 meters (e.g. The Adriatic Sea rose by about 650 meters.). That is when the Black Sea and the Mediterranean most likely became one.

This era of water disasters, earthquakes, volcanic eruptions, and tsunamis (the tsunamis at the end of the last ice age were several hundred to 2,000 meters high) resembled the biblical flood, according to some theories, and decimated over 99% of the global population.

Survivors sought refuge in newly formed living conditions, with the first such community emerging at Lepenski Vir on the border of present-day Serbia and Romania around 7000 BC. The subsequent “Climatic Optimum” created warm and humid conditions, supporting the flourishing deciduous forests that spread across the Balkan Peninsula. Remains of flora and fauna contain bones of mammals, birds, fish, snail shells. In the Balkans, from the beginning of the Neolithic to its most significant era, the Vinča culture, a whole millennium had passed.

Following that era, there was a merger of immigrants arriving from the East – specifically, from the Eastern Mediterranean, Anatolia, as well as the Middle East. These newcomers brought valuable expertise in agriculture and livestock farming. Two distinct cultures and communities harmoniously converged, laying the foundation for the advent of agriculture. As the Mesolithic era concluded, the stage was set for the emergence of a novel culture, once again marking a pioneering development in Europe – the rise to the Vinča culture, at the confluence of the Sava and the Danube.

What led to the emergence of Vinča culture?

In Europe, the primary means of fast travel for people were rivers, acting as water highways facilitating movement. The Danube played a pivotal role in the establishment of settlements in Vinča, along with the Tisa, Drava, Sava, Tamis, and their tributaries. The Morava, flowing into the Danube, served as the main route from north to south.

The practitioners of Vinča culture inhabited the right banks of the Danube. It is reasonable to assume that during the settlement’s foundation, the river spanned approximately seven kilometers in width during the spring floods. This region featured lakes and swamps, providing an advantageous environment for the development of hunting, fishing, and agriculture.

Settlements

The Neolithic settlement in Vinča is located approximately 14 km from the confluence of the Sava and the Danube. The Bolečica River, flowing into the Danube just below the settlement, served as a freshwater source and provided a connection to Avala mountain, where crucial raw materials such as cinnabarite were abundant.Vinča’s settlements are predominantly multi-layered, with nine identified in the Vinča locality itself. The earliest habitations in Vinča typically feature ellipsoid bases excavated into the loess, supporting a tent-like roof made of wicker, reeds, and straw directly on the base. The houses are organized around a central structure in a systematic manner, reminiscent of the architectural style of the Lepenski Vir culture.

Confirmation of its urban nature lies in the absence of yards attached to the houses. According to archaeologist Dragan Janković, in the first half of the Neolithic, the inhabitants engaged in food production, cultivating the land and growing cereals and other plants. In the latter half, food production surpassed immediate needs, as people successfully addressed soil depletion through fertilization. With enhanced soil fertility, a surplus of food was generated, prompting some to delve into processing, crafts, and trade – the advent of the merchant occupation.

Some of Vinča settlements exceeded in size and number of inhabitants not only all contemporary Neolithic settlements, but also the first cities that arose much later in Mesopotamia, the Aegean and Egypt.

Vinča is regarded as a city due to its continuous habitation across many generations. The population remained active year-round, and specialization of occupations was evident. Described as a metropolis, Vinča served as an economic and cultural hub, with numerous smaller settlements discovered in its immediate vicinity. There is substantial evidence of intense communication, exchange of goods, services, and people, further emphasizing its significance.

Houses

During this period, houses were crafted from wood and clay, oriented in the southeast-northwest direction, featuring quadrangular bases, vertical walls, and a gable roof. Extensive measures were taken, including leveling for stabilization, moisture insulation of the base, and painting of the walls.

The habitation culture of Vinča people reached exceptionally high standards. Their houses exhibited a remarkable level of energy efficiency, incorporating thermal insulation achieved through clay plastering. The mortar used comprised clay, sand, and chaff (straw), chosen for its crack-resistant properties, eliminating the need for mud.

Within the house, oven was employed instead of hearth, complemented by a structure resembling a smoke extractor above it. The indoor floor was crafted from wooden beams and the same plaster as the walls, but polished for easier cleaning. As the oven generated warmth, the heat permeated through the floor, providing additional comfort, so the residents could comfortably walk barefoot.

Finding Ores, Trading, and Diet

The inhabitants of Vinča were adept at processing cinnabarite, a red-colored mineral and mercury sulphide from which the only liquid metal – mercury (HgS), is extracted. This valuable resource was sourced from Avala and was highly sought after due to its rarity in nature. Additionally, they discovered malachite in Avala, renowned for its green color, and utilized it in the crafting of jewelry, as well as azurite, yielding the color blue.

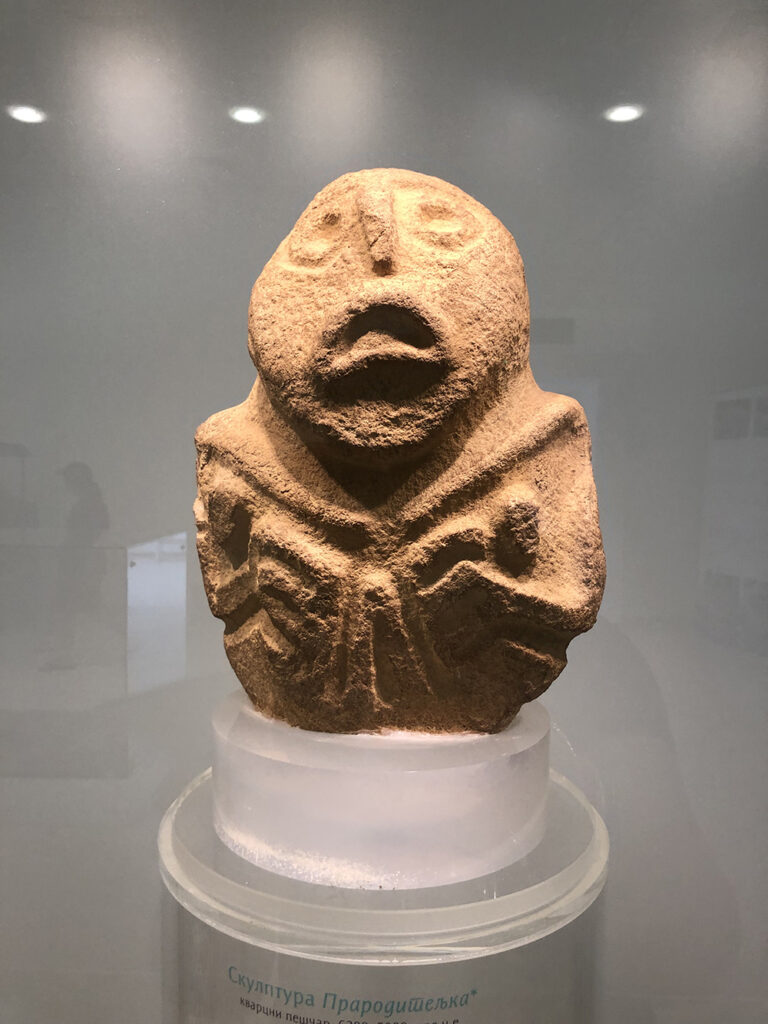

Notably, when examining Vinča figurines, one observes the absence of mouths. Professor Miloje Vasić proposed that this absence, coupled with accentuated eyes on the figurines, symbolized the protective masks worn by cinnabarite miners.

In 2010, evidence of copper smelting at high temperatures, dating back to around 5000 BC, was found in Belovode on Mount Rudnik in Serbia. This discovery solidified the Vinča culture’s status as the world’s first Copper Age culture. The people of Vinča were pioneers in copper metallurgy in Europe.

They found themselves at a crossroads, engaging in extensive trade that stretched as far as Central Europe, the Aegean, and Adriatic seas, evident by the presence of jewelry, particularly bracelets crafted from Mediterranean shells, present across the Balkans.

Their trade routes extended to the Carpathians, reaching the borders of present-day Slovakia and Hungary, where volcanic glass (obsidian) could be procured. Volcanic glass held strategic importance as a raw material for crafting sharp blades. The demand for obsidian was widespread, and during that era, it could only be found in three locations in Europe: Sicily, Milos in Greece, and the Carpathians. The people of Vinča travelled across the Tisa River valley, reaching the Carpathians and importing substantial quantities of volcanic glass to Vinča. This glass stood as the most sought-after resource of that time.

Salt was transported from Tuzla along the Bosna and Sava river valleys.

Traversing river valleys positioned Vinča as the predominant commercial, economic, and cultural center in Europe during that era. Notably, Vinča boasted the world’s oldest metallurgy, pioneering copper metallurgy in Europe.

What did they eat?

In terms of diet, the people of Vinča enjoyed a more diverse range of foods compared to contemporary diets. Paleobotanical research has found the use of barley and wheat as cereal, while legumes such as peas, vetch, and lentils were also part of their diet. Flax was cultivated for oil production. Domesticated animals, such as pork and beef, played a more significant role than wild ones.

What was the social structure of the people of Vinča? What or who did they believe in?

The crucial aspect regarding Vinča people is their peaceful coexistence throughout the Neolithic period, spanning nearly 2,000 years! This denotes an absence of organized violence within their society, even though instances of individual violence were inevitable. This is evident in the way they constructed their settlements – open and devoid of defensive walls. The absence of weapons among Vinča people further supports this observation. In individual cases of violence, the community would adopted a strategy of excommunication, effectively marginalizing such individuals.

They lived off their hard work and owned nice houses. Remarkably, there was no social stratification. It was deemed unacceptable within their culture for individuals to live off the labor of others. The leader, chosen for their extensive understanding and usefulness, bore a responsibility not only for themselves but also for the entire Vinča community. This exemplifies the elevated spiritual consciousness prevalent among the people. While lacking formal political authority, the community adhered to certain rules and upheld a shared value system.

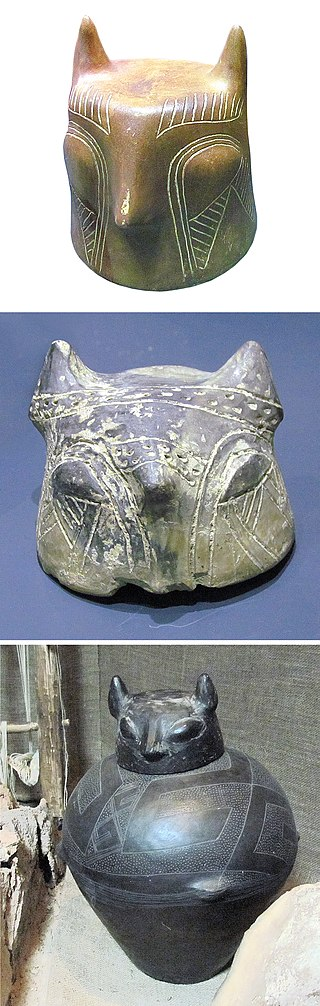

In the religious practices of Vinča people, two cults existed: the cult of mother and birth, and the cult of wakefulness, as indicated by the distinctively large eyes found on their figurines. This interpretation is shared by archaeologist Dragan Janković, curator of the Belo Brdo museum. According to Janković, these figurines predominantly depict women, symbolizing Vinča Neolithic people’s dedication to the cult of the mother, representing fertility, birth, and life. The mother figure, with her watchful gaze day and night, serves as a guardian. Various container lids adorned with big eyes and ears, protecting valuable contents, showcase a blend of human and animal features. The emphasis on alertness, reflected in the eyes and ears, signifies a guardianship role over the container’s contents. They insisted on being vigilant, and never went to war. They believed that wakefulness was closely connected to responsibility, and they were successful because they were responsible for their families, community, nature, and themselves. This stemmed from the belief that genuine love is inseparable from responsibility! Theirs was the time of true gender equality, and Vinča people valued and respected family as the fundamental unit of society.

The stylistic uniformity observed in the figurines crafted by Vinča people suggests a high level of communication and shared thought processes among them. Archaeologist Janković emphasizes their collective alertness, linking it to a sense of responsibility.

Vinča figurines also had another vital function – protectors of the household, similarly to the role of contemporary icons of saints (i.e. the saint himself is the celestial protector of a home and the occupants). In the Neolithic era, the Great Mother, symbolized by these figurines with their large eyes, assumed the role of a constant guardian.

The anthropomorphic and zoomorphic Vinča figurines, along with prosopomorphic lids and altars, showcase the remarkable artistic achievements of this culture. Noteworthy examples include the Lady of Vinča, Hyde vase, and Vidovdanka. In addition to their cultic significance, the Vinča script, composed of engraved signs, reflects the culture’s advanced development. Interpretations of these signs vary widely, ranging from indicators of ownership to bails, pictograms or pictorial letters, phonetic letters…

Vinča Script

Vinča script, also referred to as Vinča symbols, Danube script, Vinča signs, Vinča proto-writing, Vinča-Turdaș script, Old European script, etc., comprises a collection of undeciphered symbols found on various artifacts. Scholars debate whether this constitutes one of the earliest writing systems or if it serves a more symbolic purpose. The majority of these inscriptions adorn pottery, with additional occurrences on ceramic spindles, figurines, and a limited selection of other items. The symbols themselves exhibit a range of abstract and representational pictographs, including zoomorphic (animalistic) images, combs and brushes, as well as abstract symbols like swastikas, crosses, and chevrons.

Italian journalist Dr. Marco Merlini developed the Vinča inscription database called DatDas, cataloging 5,421 authentic signs. This compilation is derived from a corpus of 1,178 inscriptions featuring two or more characters and 971 inscribed artifacts. These findings hold significance since most Vinča symbols were created between 4500 and 4000 BC, compared to the symbols on the clay tablets of Tartary, believed to date from around 5300 BC. This leads to the conclusion that Vinča inscriptions predate the Proto-Sumerian pictographic script from Uruk (modern-day Iraq), considered the oldest known script, by over a thousand years. The dissimilarity between Vinča symbols and the Middle Eastern script, particularly the Sumerian script, has led to the belief that they were likely developed independently.

Despite numerous attempts to interpret the symbols, their nature and purpose remain enigmatic.

How did they bury their dead?

The burial practices of the Vinča people involved placing the deceased in a distinctive manner, commonly observed in the early Neolithic period: they were laid on their sides in a fetal position. While the specifics of their funeral rituals remain uncertain, it is noteworthy that Vinča people did not engage in the cult of hunter and did not celebrate death. Instead, their focus was on celebrating life, exemplified by their reverence for the Great Mother as a symbol of life and birth.

In lieu of conclusion

In moments of uncertainty and reflection on the complexities of life – its wars, pains, and challenges, questions of identity and purpose – one can only resort to gaze at one’s empty hands and turn to the wisdom of our ancestors for guidance. Delving into the depths of history allows us to connect with our wise, ancient forebears, and listen to the echoes of their wisdom.

And what is it that our ancient and cherished Vinča people, our remarkable ancestors, patiently convey to us?

They transform our perspectives! It is evident that they were not merely primitive, fearsome prehistoric people wielding clubs and inarticulate roars. Instead, they were people who, following the conclusion of the last ice age, pioneered the first European culture, complete with all the hallmarks of an urban lifestyle – metallurgy, script, architecture, social organization, a refined appreciation for art, trade, and more.

Vinča people have enlightened us, indicating that prehistoric people in the Neolithic era had the ability to construct houses, utilize ovens, and comprehend principles such as the golden ratio, along with the rules of contemporary architecture – embracing form, function, construction, and artistry.

The figurines left behind by Vinča people offer insight into their clothing practices, revealing that they crafted garments from finely woven fabric using thin yarn, indicative of their cultivation of flax. Upon closer examination of these exquisite figurines, one quickly discovers that women wore clothes featuring a V-neckline. This design was not only practical but also feminine, simple, and attractive..

They made ceramics of exceptional design! I am confident that many of us would desire to possess a Vinča bowl or a vase in marvelous earthy colors. They imparted the secrets of this craft to their children from an early age, demonstrating the understanding that learning is most fruitful when it takes the form of play, and that simplicity, harmony, and utility are inherently beautiful..

Vinča people were the pioneers of copper metallurgy in Europe! They had machines for drilling stone and diverse, highly precise tools. However, the most significant aspect of their existence was the non-existence of warfare. Instead, they opted for trade, fostering a society devoid of social stratification.

Contemporary humanity has positioned itself at the top of the pyramid, largely owing to advanced technology, and some individuals even perceive themselves as godlike. Through destructive actions and a detachment from God, self, and others, we destroy nature, attempting to dominate and control it through technology. The more we pursue such endeavors, the more detrimental the outcomes become, both for nature and ourselves. In contrast, the people of Vinča regarded themselves as integral parts of nature. They did not try to tame or alter nature, but instead used its power as their own.

The Vinča people also indicate the circumstances surrounding their disappearance. Around 4500 BC, after two millennia of peace, wars erupted. Why did this happen? Being the pioneers in copper smelting and metallurgy, their knowledge was passed on to others. The quest for mines ensued, recognizing the crucial importance of ores, particularly copper. However, this still wasn’t the reason enough for war as there was plenty for all. Conflicts arose when marginalized members of the community, together with immigrants, started believing it was easier to exploit others’ labor. In order to organize this, having control over resources was essential!

We can agree that this is precisely the same state in which we find the world today, with the only difference being that the number of resources is on the decline, and the rich have brought expoitation of other people’s labour to the maximum. We seem to have lost the most fundamental right – the right to a life where the well-being of all is prioritized.

We have lost the understanding of wakefulness as a responsibility, and in doing so, we have harmed not only our health but also our value system. The overall well-being of our families, communities, and entire civilizations has suffered. Therefore, as a civilization that has long been ailing, we find ourselves gradually sinking and disappearing…

But there is hope! There is always hope!

Through articles like these, our objective is to underscore the realization that technology alone is insufficient for life and survival. Without wakefulness as a responsibility, there cannot be well-being. Attaining a higher level of cognition, self-awareness, and spirituality is essential. Additionally, we aim to emphasize to our descendants the significance of respecting our, occasionally overlooked, ancestors, whose watchful, large eyes continue to oversee us even today…