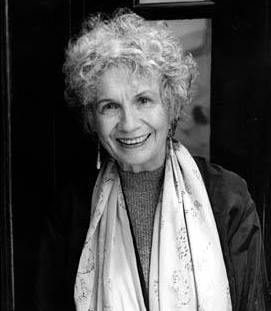

Alice Ann Munro is a Canadian short story writer who won the Nobel Prize in Literature in 2013. Munro’s work has been described as revolutionizing the architecture of short stories, especially in its tendency to move forward and backward in time. Her stories have been said to “embed more than announce, reveal more than parade.”

Munro’s fiction is most often set in her native Huron County in southwestern Ontario. Her stories explore human complexities in an uncomplicated prose style. Munro’s writing has established her as “one of our greatest contemporary writers of fiction”, or, as Cynthia Ozick put it, “our Chekhov.” Munro has received many literary accolades, including the 2013 Nobel Prize in Literature for her work as “master of the contemporary short story”, and the 2009 Man Booker International Prize for her lifetime body of work. She is also a three-time winner of Canada’s Governor General’s Award for fiction, and received the Writers’ Trust of Canada’s 1996 Marian Engel Award and the 2004 Rogers Writers’ Trust Fiction Prize for Runaway.

Early life and education

Munro was born Alice Ann Laidlaw in Wingham, Ontario. Her father, Robert Eric Laidlaw, was a fox and mink farmer, and later turned to turkey farming. Her mother, Anne Clarke Laidlaw was a schoolteacher. She is of Irish and Scottish descent; her father is a descendant of James Hogg, the Ettrick Shepherd.

Munro began writing as a teenager, publishing her first story, “The Dimensions of a Shadow”, in 1950 while studying English and journalism at the University of Western Ontario on a two-year scholarship. During this period she worked as a waitress, a tobacco picker, and a library clerk. In 1951, she left the university, where she had been majoring in English since 1949, to marry fellow student James Munro. They moved to Dundarave, West Vancouver, for James’s job in a department store. In 1963, the couple moved to Victoria, where they opened Munro’s Books, which still operates.

Career

Munro’s highly acclaimed first collection of stories, Dance of the Happy Shades (1968), won the Governor General’s Award, then Canada’s highest literary prize. That success was followed by Lives of Girls and Women (1971), a collection of interlinked stories. In 1978, Munro’s collection of interlinked stories Who Do You Think You Are? was published (titled The Beggar Maid: Stories of Flo and Rose in the United States). This book earned Munro a second Governor General’s Literary Award. From 1979 to 1982, she toured Australia, China and Scandinavia for public appearances and readings. In 1980 Munro held the position of writer in residence at both the University of British Columbia and the University of Queensland.

From the 1980s to 2012, Munro published a short-story collection at least once every four years. First versions of Munro’s stories have appeared in journals such as The Atlantic Monthly, Grand Street, Harper’s Magazine, Mademoiselle, The New Yorker, Narrative Magazine, and The Paris Review. Her collections have been translated into 13 languages. On 10 October 2013, Munro was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature, cited as a “master of the contemporary short story”. She is the first Canadian and the 13th woman to receive the Nobel Prize in Literature.

Munro is noted for her longtime association with editor and publisher Douglas Gibson. When Gibson left Macmillan of Canada in 1986 to launch the Douglas Gibson Books imprint at McClelland and Stewart, Munro returned the advance Macmillan had already paid her for The Progress of Love so that she could follow Gibson to the new company. Munro and Gibson have retained their professional association ever since; when Gibson published his memoirs in 2011, Munro wrote the introduction, and to this day Gibson often makes public appearances on Munro’s behalf when her health prevents her from appearing personally.

Almost 20 of Munro’s works have been made available for free on the web, in most cases only the first versions. From the period before 2003, 16 stories have been included in Munro’s own compilations more than twice, with two of her works scoring four republications: “Carried Away” and “Hateship, Friendship, Courtship, Loveship, Marriage”.

Film adaptations of Munro’s short stories have included Martha, Ruth and Edie (1988), Edge of Madness (2002), Away from Her (2006), Hateship, Loveship (2013) and Julieta (2016).

Writing

Many of Munro’s stories are set in Huron County, Ontario. Her strong regional focus is one of her fiction’s features. Asked after she won the Nobel Prize, “What can be so interesting in describing small town Canadian life?” Munro replied, “You just have to be there!” Another feature is an omniscient narrator who serves to make sense of the world. Many compare Munro’s small-town settings to writers from the rural American South. As in the works of William Faulkner and Flannery O’Connor, Munro’s characters often confront deep-rooted customs and traditions, but her characters’ reactions are generally less intense than their Southern counterparts’. Her male characters tend to capture the essence of the everyman, while her female characters are more complex. Much of Munro’s work exemplifies the Southern Ontario Gothic literary genre.

Munro’s work is often compared with the great short-story writers. In her stories, as in Chekhov’s, plot is secondary and “little happens”. As in Chekhov, Garan Holcombe says, “All is based on the epiphanic moment, the sudden enlightenment, the concise, subtle, revelatory detail.” Munro’s work deals with “love and work, and the failings of both. She shares Chekhov’s obsession with time and our much-lamented inability to delay or prevent its relentless movement forward.”

A frequent theme of her work, particularly in her early stories, has been the dilemmas of a girl coming of age and coming to terms with her family and her small hometown. In recent work such as Hateship, Friendship, Courtship, Loveship, Marriage (2001) and Runaway (2004) she has shifted her focus to the travails of middle age, women alone, and the elderly. Her characters often experience a revelation that sheds light on, and gives meaning to, an event.

Munro’s prose reveals the ambiguities of life: “ironic and serious at the same time,” “mottoes of godliness and honor and flaming bigotry,” “special, useless knowledge,” “tones of shrill and happy outrage,” “the bad taste, the heartlessness, the joy of it.” Her style juxtaposes the fantastic and the ordinary, with each undercutting the other in ways that simply and effortlessly evoke life.

Many critics have written that Munro’s stories often have the emotional and literary depth of novels. Some have asked whether Munro actually writes short stories or novels. Alex Keegan, writing in Eclectica, gave a simple answer: “Who cares? In most Munro stories there is as much as in many novels.”

Research on Munro’s work has been undertaken since the early 1970s, with the first PhD thesis published in 1972. The first book-length volume collecting the papers presented at the University of Waterloo first conference on her work was published in 1984, The Art of Alice Munro: Saying the Unsayable. In 2003/2004, the journal Open Letter. Canadian quarterly review of writing and sources published 14 contributions on Munro’s work. In autumn 2010, the Journal of the Short Story in English (JSSE)/Les cahiers de la nouvelle dedicated a special issue to Munro, and in May 2012 an issue of the journal Narrative focussed on a single story by Munro, “Passion” (2004), with an introduction, summary of the story, and five analytical essays.

Creating new versions

Munro publishes variant versions of her stories, sometimes within a short span of time. Her stories “Save the Reaper” and “Passion” came out in two different versions in the same year, in 1998 and 2004 respectively. Two other stories were republished in a variant version about 30 years apart, “Home” (1974/2006/2014) and “Wood” (1980/2009).

In 2006 Ann Close and Lisa Dickler Awano reported that Munro had not wanted to reread the galleys of Runaway (2004): “No, because I’ll rewrite the stories.” In their symposium contribution An Appreciation of Alice Munro they say that of her story “Powers”, for example, Munro did eight versions in all.

Section variants of “Wood”.

Awano writes that “Wood” is a good example of how Munro, “a tireless self-editor”, rewrites and revises a story, in this case returning to it for a second publication nearly 30 years later, revising characterizations, themes and perspectives, as well as rhythmic syllables, a conjunction or a punctuation mark. The characters change, too. Inferring from the perspective they take on things, they are middle-age in 1980, and in 2009 they are older. Awano perceives a heightened lyricism brought about not least by the poetic precision of the revision Munro undertakes. The 2009 version comprises eight sections to the 1980 version’s three, and has a new ending. Awano writes that Munro literally “refinishes” the first take on the story with an ambiguity characteristic of Munro’s endings, and that Munro reimagines her stories throughout her work a variety of ways.

Several stories were republished with considerable variation as to which content goes into which section. This can be seen, for example, in “Home”, “The Progress of Love”, “What Do You Want to Know For?”, “The Children Stay”, “Save the Reaper”, “The Bear Came Over the Mountain”, “Passion”, “The View From Castle Rock”, “Wenlock Edge”, and “Deep-Holes”.

Personal life

She married James Munro in 1951. Their daughters Sheila, Catherine, and Jenny were born in 1953, 1955, and 1957, respectively; Catherine died the day of her birth due to the lack of functioning kidneys.

In 1963, the Munros moved to Victoria, where they opened Munro’s Books, a popular bookstore still in business. In 1966, their daughter Andrea was born. Alice and James Munro divorced in 1972.

Munro returned to Ontario to become writer in residence at the University of Western Ontario, and in 1976 received an honorary LLD from the institution. In 1976, she married Gerald Fremlin, a cartographer and geographer she met in her university days. The couple moved to a farm outside Clinton, Ontario, and later to a house in Clinton, where Fremlin died on 17 April 2013, aged 88. Munro and Fremlin also owned a home in Comox, British Columbia.

At a Toronto appearance in October 2009, Munro indicated that she had received treatment for cancer and for a heart condition requiring coronary-artery bypass surgery.

In 2002, Sheila Munro published a childhood memoir, Lives of Mothers and Daughters: Growing Up with Alice Munro.

Works

Original short-story collections:

– Dance of the Happy Shades – 1968 (winner of the 1968 Governor General’s Award for Fiction

– Lives of Girls and Women – 1971 (winner of the Canadian Bookseller’s Award)

– Something I’ve Been Meaning to Tell You – 1974

– Who Do You Think You Are? – 1978 (winner of the 1978 Governor General’s Award for Fiction; also published as The Beggar Maid; short-listed for the Booker Prize for Fiction in 1980)

– The Moons of Jupiter – 1982 (nominated for a Governor General’s Award)

– The Progress of Love – 1986 (winner of the 1986 Governor General’s Award for Fiction)

– Friend of My Youth – 1990 (winner of the Trillium Book Award)

– Open Secrets – 1994 (nominated for a Governor General’s Award)

– The Love of a Good Woman – 1998 (winner of the 1998 Giller Prize and the 1998 National Book Critics Circle Award)

– Hateship, Friendship, Courtship, Loveship, Marriage – 2001 (republished as Away from Her)

– Runaway – 2004 (winner of the Giller Prize and Rogers Writers’ Trust Fiction Prize)

– The View from Castle Rock – 2006

– Too Much Happiness – 2009

– Dear Life – 2012

Short-story compilations:

– Selected Stories (later retitled Selected Stories 1968–1994 and A Wilderness Station: Selected Stories, 1968–1994) – 1996

– No Love Lost – 2003

– Vintage Munro – 2004

– Alice Munro’s Best: A Selection of Stories – Toronto 2006 / Carried Away: A Selection of Stories – New York 2006; both 17 stories (spanning 1977–2004) with an introduction by Margaret Atwood

– My Best Stories – 2009

– New Selected Stories – 2011

– Lying Under the Apple Tree. New Selected Stories, 434 pages, 15 stories, c Alice Munro 2011, Vintage, London 2014, paperback

– Family Furnishings: Selected Stories 1995–2014 – 2014