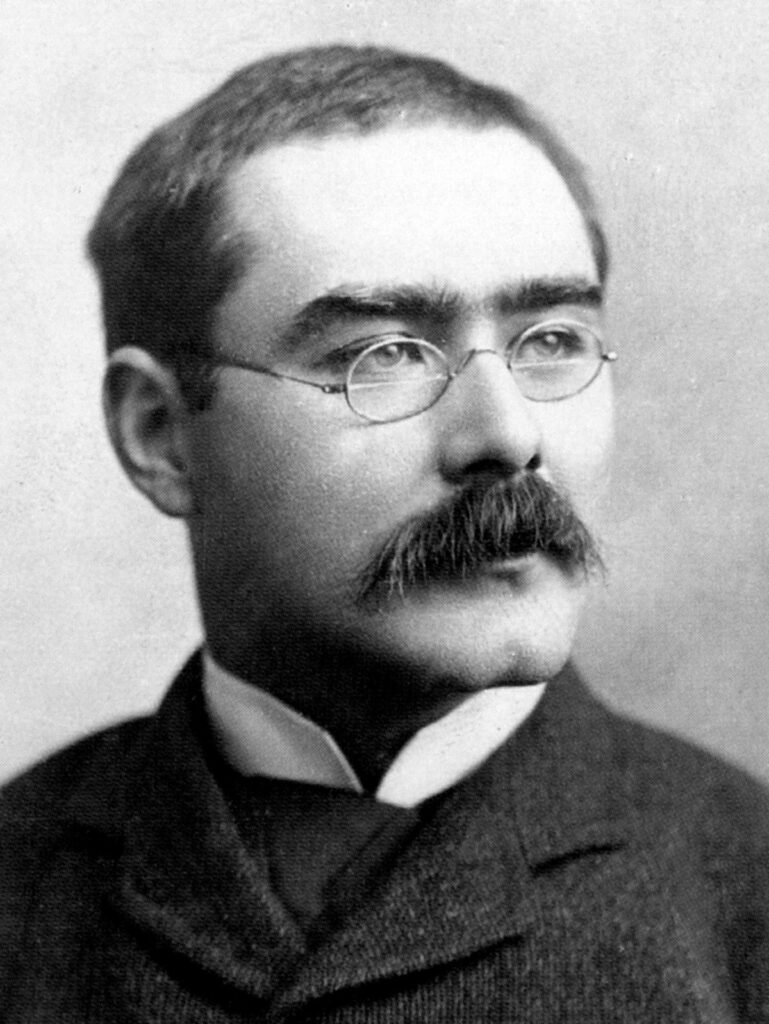

Joseph Rudyard Kipling (December 30, 1865 – January 18, 1936) was an English novelist, short-story writer, poet, and journalist. He received the 1907 Nobel Prize in Literature.

Kipling’s works of fiction include the Jungle Book duology (The Jungle Book, 1894; The Second Jungle Book, 1895), Kim (1901), the Just So Stories (1902) and many short stories, including “The Man Who Would Be King” (1888). His poems include “Mandalay” (1890), “Gunga Din” (1890), “The Gods of the Copybook Headings” (1919), “The White Man’s Burden” (1899), and “If—” (1910). He is seen as an innovator in the art of the short story. His children’s books are classics; one critic noted “a versatile and luminous narrative gift”.

Kipling in the late 19th and early 20th centuries was among the United Kingdom’s most popular writers. Henry James said “Kipling strikes me personally as the most complete man of genius, as distinct from fine intelligence, that I have ever known.” In 1907, he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature, as the first English-language writer to receive the prize, and at 41, its youngest recipient to date. He was also sounded out for the British Poet Laureateship and several times for a knighthood, but declined both. Following his death in 1936, his ashes were interred at Poets’ Corner, part of the South Transept of Westminster Abbey.

Kipling’s subsequent reputation has changed with the political and social climate of the age. The contrasting views of him continued for much of the 20th century. Literary critic Douglas Kerr wrote: “[Kipling] is still an author who can inspire passionate disagreement and his place in literary and cultural history is far from settled. But as the age of the European empires recedes, he is recognised as an incomparable, if controversial, interpreter of how empire was experienced. That, and an increasing recognition of his extraordinary narrative gifts, make him a force to be reckoned with.”

Childhood

Joseph Rudyard Kipling was born on December 30, 1865, in Bombay (now called Mumbai), India.

At the time of his birth, his parents, John and Alice, were recent arrivals in India as part of the British Empire. They met in 1863 and courted at Rudyard Lake in Rudyard, Staffordshire, England. They married and moved to India in 1865 after John Lockwood had accepted the position as Professor at the School of Art. They had been so moved by the beauty of the Rudyard Lake area that they named their first child after it, Joseph Rudyard.

The family lived well, and Kipling was especially close to his mother. His father, an artist, was the head of the Department of Architectural Sculpture at the Jeejeebhoy School of Art in Bombay.

For Kipling, India was a wondrous place. Along with his younger sister, Alice, he reveled in exploring the local markets with his nanny. He learned the language and, in this bustling city of Anglos, Muslims, Hindus, Buddhists and Jews, connected with the country and its culture.

However, at the age of six, Kipling’s life was torn apart when his mother, wanting her son to receive a formal British education, sent him to Southsea, England, where he attended school and lived with a foster family named the Holloways.

These were hard years for Kipling. Mrs. Holloway was a brutal woman who quickly grew to despise her foster son. She beat and bullied the youngster, who also struggled to fit in at school. His only break from the Holloways came in December, when Kipling, who told nobody of his problems at school or with his foster parents, traveled to London to stay with relatives for the month.

Kipling’s solace came in books and stories. With few friends, he devoted himself to reading. He particularly adored the work of Daniel Defoe, Ralph Waldo Emerson and Wilkie Collins. When Mrs. Holloway took away his books, Kipling snuck in literature time, pretending to play in his room by moving furniture along the floor while he read.

By the age of 11, Kipling was on the verge of a nervous breakdown. A visitor to his home saw his condition and immediately contacted his mother, who rushed back to England and rescued her son from the Holloways. To help relax his mind, Alice took her son on an extended vacation and then placed him in a new school in Devon. There, Kipling flourished and discovered his talent for writing, eventually becoming editor of the school newspaper.

Return to India

In 1882, Kipling returned to India. It was a powerful time in the young writer’s life. The sights and sounds, even the language, which he’d believed he’d forgotten, rushed back to him upon his arrival.

Kipling made his home with his parents in Lahore and, with his father’s help, found a job with a local newspaper. The job offered Kipling a good excuse to discover his surroundings. Nighttime, especially, proved to be valuable for the young writer. Kipling was a man of two worlds, somebody who was accepted by both his British counterparts and the native population. Suffering from insomnia, he roamed the city streets and gained access to the brothels and opium dens that rarely opened their doors to common Englishmen.

Kipling’s experiences during this time formed the backbone for a series of stories he began to write and publish. They were eventually assembled into a collection of 40 short stories called Plain Tales From the Hills, which gained wide popularity in England.

In 1889, seven years after he had left England, Kipling returned to its shores in hopes of leveraging the modest amount of celebrity his book of short stories had earned him. In London, he met Wolcott Balestier, an American agent and publisher who quickly became one of Kipling’s great friends and supporters. The two men grew close and even traveled together to the United States, where Balestier introduced his fellow writer to his childhood home of Brattleboro, Vermont.

Life in America

Around this time, Kipling’s star power started to grow. In addition to Plain Tales From the Hills, Kipling published a second collection of short stories, Wee Willie Winkie (1888), and American Notes (1891), which chronicled his early impressions of America. In 1892, he also published the poetry work Barrack-Room Ballads.

Kipling’s friendship with Balestier changed the young writer’s life. He soon got to know Balestier’s family, in particular, his sister, Carrie. The two appeared to be just friends, but during the Christmas holiday in 1891, Kipling, who had traveled back to India to see his family, received an urgent cable from Carrie. Wolcott had died suddenly of typhoid fever and Carrie needed Kipling to be with her.

Kipling rushed back to England, and within eight days of his return, On 18 January 1892, Carrie Balestier (aged 29) and Rudyard Kipling (aged 26) married in London, in the “thick of an influenza epidemic, when the undertakers had run out of black horses and the dead had to be content with brown ones.” The wedding was held at All Souls Church in Langham Place, central London. Henry James gave away the bride.

Following their wedding, the Kiplings set off on an adventurous honeymoon that took them to Canada and then Japan. But as was often the case in Kipling’s life, good fortune was accompanied by hard luck. During the Japanese leg of the journey, Kipling learned that his bank, the New Oriental Banking Corporation, had failed. The Kiplings were broke.

Left only with what they had with them, the young couple decided to travel to Brattleboro, where much of Carrie’s family still resided. Kipling fell in love with life in the states, and the two decided to settle there. In the spring of 1891, the Kiplings purchased from Carrie’s brother Beatty a piece of land just north of Brattleboro and had a large home constructed, which they called the Naulahka.

Kipling seemed to adore his new life, which soon saw the Kiplings welcome their first child, a daughter named Josephine (born in 1893), and a second daughter, Elsie (born in 1896). A third child, John, was born in 1897, after the Kiplings had left America.

As a writer, too, Kipling flourished. His work during this time included The Jungle Book (1894), The Naulahka: A Story of West and East (1892) and The Second Jungle Book (1895), among others. Kipling was delighted to be around children—a characteristic that was apparent in his writing. His tales enchanted girls and boys all over the English-speaking world.

But life again took another dramatic turn for the family when Kipling had a major falling out with Beatty. The two men quarreled, and when Kipling made noise about taking his brother-in-law to court because of threats Beatty had made to his life, newspapers across America broadcast the spat on their front pages.

The gentle Kipling was embarrassed by the attention and regretful of how his celebrity had worked against him. As a result, in 1896, he and his family left Vermont for a new life back in England.

Family Tragedy

In the winter of 1899, Carrie, who was homesick, decided that the family needed to travel back to New York to see her mother. But the journey across the Atlantic was brutal, and New York was frigid. Both Kipling and young Josephine arrived in the states gravely ill with pneumonia. For days, the world kept careful watch on the state of Kipling’s health as newspapers reported on his condition.

Kipling did recover, but his beloved Josephine did not. The family waited until Kipling was strong enough to hear the news, but even then, Carrie could not bear to break it to him, asking his publisher, Frank Doubleday, to do so instead. To those who knew him, it was clear that Kipling never recovered from Josephine’s death. He vowed never to return to America.

Over time, Kipling would become known for harboring a sense of English imperialism and views on certain cultures that would draw much objection and be seen as disturbingly racist. Yet even as Kipling grew more rigid in his viewpoints as he got older, aspects of his earlier work would still be celebrated.

Life in England

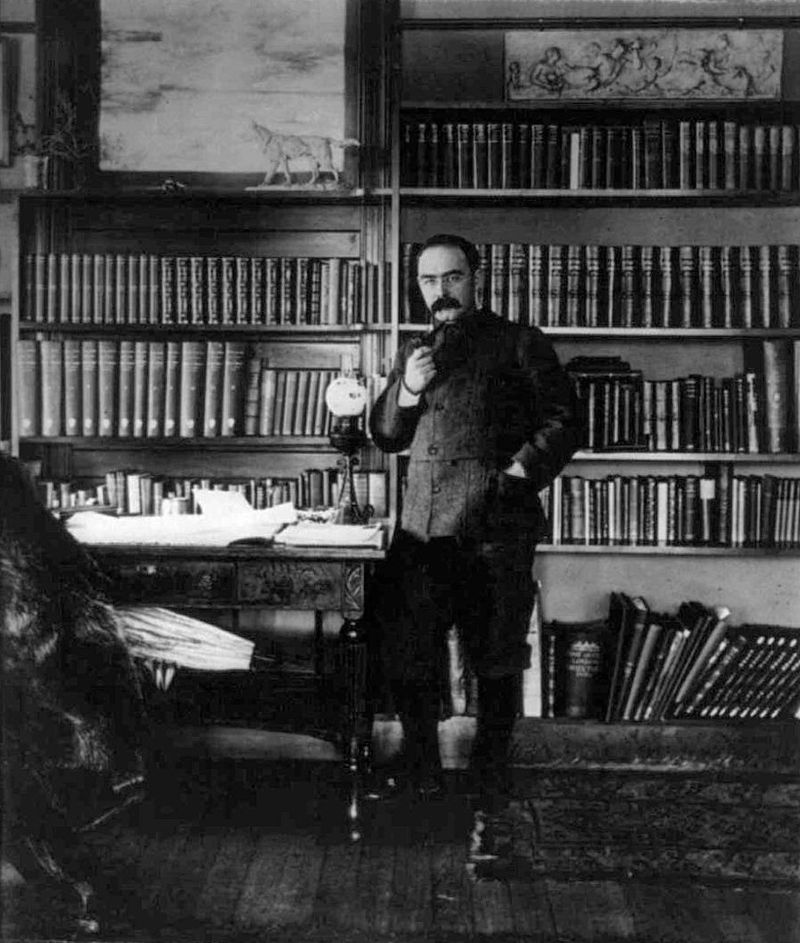

The turn of the century saw the publication of another novel that would become quite popular, Kim (1901), which featured a youth’s adventure on the Grand Trunk Road. In 1902, the Kiplings bought a large estate in Sussex known as Bateman’s. The property had been erected in 1634, and for the private Kiplings, it offered the kind of isolation they now cherished. Kipling revered the new home, with its lush gardens and classic details. “Behold us,” he wrote in a November 1902 letter, “lawful owners of a grey stone, lichened house—A.D. 1634 over the door—beamed, paneled, with old oak staircase and all untouched and unfaked.”

At Bateman’s, Kipling found some of the happiness he thought he had forever lost following the death of Josephine. He was dedicated as ever to his writing, something Carrie helped ensure. Adopting the role of the head of the household, she held reporters at bay when they came calling and issued directions to both staff and children.

Kipling’s books during his years at Bateman’s included Puck of Pook’s Hill (1906), Actions and Reactions (1909), Debts and Credits (1926), Thy Servant a Dog (1930) and Limits and Renewals (1932).

The same year he purchased Bateman’s, Kipling also published his Just So Stories, which were greeted with wide acclaim. The book itself was in part a tribute to his late daughter, for whom Kipling had originally crafted the stories as he put her to bed. The book’s name had, in fact, come from Josephine, who told her father he had to repeat each tale as he always had, or “just so,” as Josephine often said.

World War I

As much of Europe braced for war with Germany, Kipling proved to be an ardent supporter of the fight. In 1915, he even traveled to France to report on the war from the trenches. He also encouraged his son, John, to enlist. Since Josephine’s death, Kipling and John had grown tremendously close.

Wanting to help his son enlist, Kipling drove John to several different military recruiters. But plagued with the same eyesight problems his father had, John was repeatedly turned down. Finally, Kipling made use of his connections and managed to get John enlisted with the Irish Guard as a second lieutenant.

In October 1915, the Kiplings received word that John had gone missing in France. The news devastated the couple. Kipling, perhaps feeling guilty about his push to make his son a soldier, set off for France to find John. But nothing ever came of the search, and John’s body was never recovered. A distraught and drained Kipling returned to England to once again mourn the loss of a child.

Final Years and Death

While Kipling continued to write for the next two decades, he never again returned to the bright, cheery children’s tales he had once so delighted in crafting. Health issues eventually caught up to both Kipling and Carrie, the result of age and grief.

Over his last few years, Kipling suffered from a painful ulcer that eventually took his life on January 18, 1936. Kipling’s ashes were buried in Westminster Abbey in Poets’ Corner next to the graves of Thomas Hardy and Charles Dickens.

_______________

If—

Analysis:

Rudyard Kipling’s poem “If—” presents a series of challenging conditions that test an individual’s character and resilience. It serves as a guide to moral conduct, emphasizing the importance of maintaining composure, self-belief, patience, integrity, and perseverance in the face of adversity.

The poem consists of four stanzas, each containing six lines. Each stanza begins with the conditional phrase “If you can,” followed by a specific challenge or trial. The speaker addresses an unnamed individual, often referred to as “my son,” imparting wisdom and guidance on how to navigate life’s complexities.

Kipling explores various virtues and challenges that an individual may encounter. These include maintaining composure and self-control amidst chaos and blame, trusting oneself while acknowledging others’ doubts, waiting patiently without succumbing to weariness or dishonesty, and resisting the temptations of hatred and pride.

The poem also emphasizes the importance of balance and moderation. The speaker advises the individual to dream and think creatively but not let these pursuits consume them. They should strive for success and triumph but not let these achievements define their worth.

Another significant theme is resilience and perseverance. The speaker encourages the individual to endure hardships, setbacks, and disappointments without losing hope. They should be willing to rebuild and start anew, even after facing significant losses.

The poem concludes with a powerful affirmation of the individual’s potential. If they can successfully meet all these challenges, they will possess the Earth, achieve true manhood, and embody the qualities that define a virtuous and exemplary human being.

Overall, “If—” is a timeless and inspiring poem that offers profound insights into the qualities and values that contribute to a meaningful and fulfilling life. It challenges readers to reflect on their own character and strive for moral excellence, resilience, and unwavering determination in the pursuit of their goals and aspirations.