Interview – Angela Talic

Author: Natasa Dinic

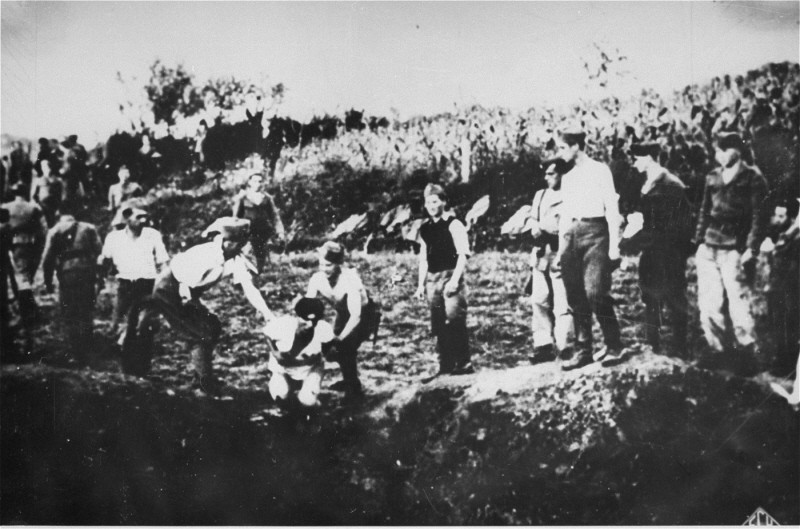

Almost everyone in the world has heard about Auschwitz, a place in Poland where approximately 1.1 million people were murdered by the Nazis. But how many people have heard about Jasenovac concentration and extermination camp, established by the authorities of the Independent State of Croatia (NDH) and Ustaše regime, in occupied Yugoslavia during the WW II?

We had a great pleasure to interview Angela Talic, a recent UBC law graduate, who, for the first time in the history of Allard School of Law at University of British Columbia in Vancouver, wrote a comparative paper of Auschwitz and Jasenovac.

What prompted you to write an essay “Recognizing the Wrongs of the Past: The Influence of Auschwitz and Jasenovac on International Criminal Law”?

During my second year at law school, I enrolled in International Criminal Law. I found the topic of International Criminal Law thought-provoking; the legitimacy of this field of law is constantly under scrutiny. Does international criminal law make a difference? Will the International Criminal Court (ICC) succeed as a project? While discussing WW II and its contributions to the field, my professor mentioned his interest in the fact that Germany had become the most contrite nation in the world, and there was very little literature regarding the Auschwitz Trials of 1963-1965. He recommended several books concerning the Auschwitz Trials, and I started reading. Originally, I planned to write a paper on Auschwitz for my third year Directed Studies.

I was discussing my research with my brother when he raised the topic of Jasenovac in Croatia. I had never even heard about Jasenovac. I was intrigued so I googled the Ustaša party and Jasenovac. The more I read, the more I began to understand the history of the contention between the Serbians and Croatians. Additionally, it seemed odd that concentration camps outside of Germany occupied territory were rarely discussed in terms of WW II. I decided I would incorporate a comparison of Auschwitz and the “Auschwitz of the Balkans” into my paper as it would give me an opportunity to learn more about Jasenovac.

Where did your interest in the theme of wars, and Jasenovac in particular, come from?

I have had a keen interest in World War II since I was a teenager. Even as a teenager, I could never comprehend how the Holocaust was permitted to take place. I questioned how the German people, the Polish people, and the world, in general, stood by and let Hitler and the Nazis exterminate the Jews of Europe. To this day, I love to read books about WW II and watch movies and documentaries on conflicts.

Given that my ethnic background is Serbian, I felt the need to educate myself about Jasenovac once I was aware of its existence. I wanted to know more about the tensions that has plagued the relationships between former Yugoslavians.

Has anyone at UBC (University of British Columbia) written on the topic of Auschwitz and Jasenovac before?

To my knowledge, a comparative paper of Auschwitz and Jasenovac has not been written prior to this at UBC. Auschwitz has come to represent the Holocaust, yet very few people have any knowledge concerning Jasenovac. Holocaust denial has become a crime in many countries, whereas, the existence of Jasenovac as an extermination camp continues to be refuted in particular circles.

Many students at Peter A. Allard School of Law at the University of British Columbia say that is not easy to get A+ for essay. Some say it is almost impossible, but you, did it! Could you tell us more about the process of writing your essay?

I originally sought to write a paper on the Auschwitz Trials of 1963-1965 to meet the requirements for a Directed Studies pertaining to International Criminal Law. I had asked my supervising Professor whether he had any recommendations regarding titles of books written on the subject. He recommended three titles, which I ordered immediately. I read each book twice over the summer prior to the school semester. It was during this time that I recognized the contrast between the perceived justice attained for the victims of Auschwitz versus Jasenovac, and the legacy of a mass trial on the nations. Essentially, the importance of recognizing the past. There was little literature available on Jasenovac, thus, I had to research and order a few books that were not available at any local library.

I entered the Peter A. Allard School of Law at the University of British Columbia with a background in science and accounting; two fields of study that did not provide much experience in writing papers. If I learned one thing through my time at law school, it was the importance of creating a solid, detailed outline prior to writing a paper, which is a skill in itself. I slowly created a very detailed outline for the paper. My professor also reminded me of the importance of addressing any opposing arguments to the one I wished to pursue. I also kept in mind that law school professors seemed to appreciate unique arguments or topics. Keeping these concepts in mind, I spent hours writing and reviewing my paper “Recognizing the Wrongs of the Past: The Influence of Auschwitz and Jasenovac on International Criminal Law.” I never anticipated I would receive such a distinctive grade on my paper.

Was it difficult to find credible sources? What sources did you use the most in your paper?

Indisputably, the volume of research material pertaining to the Nazi regime and Auschwitz far surpasses the amount of information available regarding the Ustaša regime and Jasenovac. From the beginning, I realized it would be an effort to accumulate enough information regarding Jasenovac, which would serve as the basis of a research paper. Google searches proved futile; they provided minimal information. I was able to locate a few pertinent English academic papers through the online UBC Library catalogue. There are several papers available, but many are in Serbo-Croatian, and I lack the proficiency in Serbo-Croatian to analyze academic arguments or understand the vocabulary associated with war.

The First International Conference and Exhibition on the Jasenovac Concentration Camp was held at Kingsborough Community College of the City University of New York in Brooklyn, New York from October 29 to 31, 1997. The proceedings of the conference were published in a compilation titled Jasenovac and the Holocaust in Yugoslavia: Analyses and Survivor Testimonies Presented at the First International Conference and Exhibition on the Jasenovac Concentration Camp, and edited by Barry Lutchy. This book provides academic perspectives on the total numbers of victims, historical data, and survivor testimonies. It was an excellent resource for my paper. I searched the catalogues of local libraries, but print books were non-existent. My best resource for obtaining books was purchasing them through Amazon.

To what extent did the failure to clear up various crimes and genocides during the Second World War, from 1941 to 1945, affect the commencement of Yugoslav Civil War in 1991? Has the international community missed that segment?

The denial of the Jasenovac genocide is a blatant example of a state’s rejection of its own past. The “Jasenovac Lie” has played a prominent and active role in the Serbian-Croatian ethnic relations. “In the name of ‘Bratstvo i Jedinstvo’ (Brotherhood and Unity), and for a variety of other reasons, Tito’s Yugoslavia failed to come to grips with the legacy of Jasenovac and the Holocaust. It failed to denazify the country. It failed to force Croats, Muslims and Albanians and other collaborators to face their crimes in way that would allow the peoples to really achieve ‘Bratstvo i Jedinstvo’”.[1] Tito’s Yugoslavia suppressed the recognition of the NDH perpetrated genocide, and the silence created incomprehension and deep-rooted resentment, rather than the unity and brotherhood Tito envisioned.

The basis for the collapse of Yugoslavia is a dissonance with deep roots stemming from both world wars. Jasenovac perpetuated historically rooted ethnic hatred, religious intolerance, and fierce nationalism on all sides. This deep-rooted resentment served as a precursor to the Balkan Wars. The unresolved traumatic effects of the events of the wars, including Jasenovac, were passed to later generations, which can be coined as intergenerational trauma. This historical trauma led to cumulative impact across cultures; later generations developed a sense of obligation to grieve, and reverse the humiliation pertaining to the historical trauma. Tito’s death in 1980 and the rapid disintegration of the ruling League of Communists of Yugoslavia in the first months of 1990 resulted in a power vacuum and the re-emergence of national parties throughout the country. Ethnic-national identity became the foundational basis for the establishment of the principal parties: the Croat Democratic Union (HDZ), the Party for Democratic Action (SDA) and the Serbian Democratic Party (SDS). Communism could no longer suppress the tensions associated with the past. Josip Sopta, a priest and historian, contends that the failure of Communists to publicly acknowledge the realistic number of Ustaša victims and the related atrocities was the leading precipitating factor to the wars in the 1990s.

This became apparent in the proceedings that took place in front of the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY), a United Nations court of law that dealt with war crimes that took place during the conflicts in the Balkans in the 1990s. Tribunal transcripts commonly include a general background to the Balkan Wars, which reference the Ustaša regime and Jasenovac. The topic of Jasenovac emerged at numerous points in testimony and the respective arguments of States before the ICTY and the ICJ; it has been instrumentalized for propaganda purposes and the provoking of endless debates.

It also notable that during the prosecution of Serbian war criminals, the ICTY was not concerned with the questions of who started the war, how many Serbs were killed, and what crimes were committed against Serbs prior to when they entered into the war. “For example, Serbs were accused and convicted of genocide of Srebrenica, regardless of the fact that over a thousand Serb civilians, approximately 1600, living in close proximity to Srebrenica were cruelly slaughtered by Muslims from Srebrenica, at a time prior to the Serbian offensive.” Yet, neither the international nor the domestic legal community prosecuted the crimes of the Ustaše against the Serbs during the Second World War with the same determination. The failure to recognize the atrocities of the past, and imbalanced focus on the offences committed by the Serbs during the Balkan Wars, has perpetuated the victimhood experienced by the Serbian nation.

Would the views of the international community have been different if the issue of Jasenovac and other concentration camps and massacres had long ago been handed over to the International Tribunal?

History indicates that the confrontation of the past is a requisite to sustaining peace and improving relations. The international community mandated that Germany confronted its Nazi past, and it initiated the process through the Nuremberg trials. Nevertheless, history has shown that criminal convictions against individual perpetrators fails to provide conventional justice to the victims of international crimes, including genocide. The Nuremberg trials, the Eichmann trial and even the ICTY provided little in terms of redress or compensation for the victims of war crimes, crimes against humanity or genocide. However, mass trials for mass violence serve a pedagogical purpose and the recognition and validation of genocide serves as the fundamental step towards reconciliation, mitigated the need to attain revenge.

The international community was unrelenting in its prosecution of Nazis. The majority of Germans viewed themselves as victims, and this attitude led to the objection of the legitimacy of the Nuremberg trials, which they criticized as no more than victor’s justice.

The Frankfurt Auschwitz Trial of 1963 was a major turning point for Holocaust survivors, war criminals, the German population and the international legal community. The Auschwitz trial cultivated international awareness of the complicity of the German population in the undertaking of the Final Solution, particularly in regard to the industrialized extermination executed at Auschwitz. Furthermore, Nazi crimes were tried under German law by a German judiciary, negating an argument of victor’s justice. By means of humiliation and guilt, Germany was compelled to confront the atrocities of its past, which led to the development of a distinct sense of contriteness.

Had Yugoslavia followed a similar path following the Second World War, there is a greater probability that ethnic tensions may have been subdued and a path towards reconciliation may have been initiated prior to the eruption of the 1990s Civil War. Tito’s vision of a reunited Yugoslavia repressed the recognition of the ethnic cleansing, and the atrocities of the Ustaše were not prosecuted on a domestic level. Taking into consideration the historical prosecution of Nazis and its effects on the collective responsibility of the German population, international intervention in the pursuit of justice should have been extended to all victims of war crimes associated with the Second World War. The international community disregarded the victims of the Ustaša regime and inadvertently perpetuated the institutionalized racial discrimination that fuelled the atrocities of the war. The aphorism, “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it” is accredited to the Spanish philosopher George Santayana. The past of Yugoslavia was repeated during the 1990s Civil War. It can be assumed that the international community recognized its failure to enhance justice and reconciliation following the demise of the Ustaša regime, and thus, created an international tribunal to pursue justice following the Civil War in the wake of the recognition of its initial mistake.

This year you’ve graduated from the Allard School of Law at University of British Columbia in Vancouver. What are your plans?

In September 2021, I will begin a one year articling term with Koskie Glavin Gordon LPP in Vancouver. They are a boutique firm specializing in labour law, pensions and benefits, insolvency, class actions, human rights and employee-side general litigation.

I have worked as a Longshore Worker in the Port of Vancouver since 2007. As a member of the International Longshore and Warehouse Union (“ILWU”), I have served my union in the capacity of the Executive Committee, Human Rights Committee, Grievance Committee, and most recently, ILWU Canada Workplace Violence and Harassment Prevention Coordinator. I possessed a strong interest in uniting my labour background with my future legal career by pursuing a career in union-side labour law. An articling position with Koskie Glavin Gordon will allow me to gain a deeper understanding of the legal dimensions associated with trade unionist activism while supporting unions that represent thousands of Canadians across all sectors. I believe personal development and growth are contingent on remaining curious and continual learning, and this articling opportunity presents a paramount opportunity to expand my skills and knowledge within federal and provincial workplace law and advocacy, and human rights law.

Once I complete the articling requirement, we will see what the future holds.

What is your cradle?

My son, and providing him with a plethora of opportunities and experiences. We love to travel, especially to sun soaked destinations. I want him to be independent, and to know that nothing is beyond his reach if he dedicates himself to achieving his goals.

In addition, I love books. Reading allows me to relax and to acquire new knowledge.

Dear Angela, thank you for this amazing interview.

The Cradle Magazine wish you all the best in your personal and professional life.

[1] Barry M Lituchy, ed, Jasenovac and the Holocaust in Yugoslavia: Analyses and Survivor Testimonies Presented at the First International Conference and Exhibition on the Jasenovac Concentration Camp (New York: Jasenovac Research Institute, 2006) at liii.

Read the whole paper here:

Congratulations Angela, this is a thoughtful and deeply insightful study that will hopefully be helpful in informing human rights law to help correct past wrongs. And serve as a guide post to those seeking ways to end division and secularism to build better connections in communities and countries. Thank you